ACT for Social Justice, based in Brattleboro, VT, published the below account of mine--which I'm sharing here as well. If you're looking or know someone who's looking for social justice support, I strongly suggest checking them out! From their homepage:

Do you want a world where all people have what they need to thrive? Equity is important in making this possible. It means that people put in what they can and get back what they need. ACT provides strategies and tools for putting equity into practice.

***

From the

introductory handout at ACT for Social Justice’s racial justice workshop

series:

In this workshop series we will look at our own

understanding of race & racism and how that impacts the way we talk with

our children about race. … Our main goals are for participants to:

·

Gain a

deeper understanding of race/racism/white supremacy/racial justice

·

Build

relationships that allow for better communication about the above concepts

·

Set the

foundation to work together for racial justice

·

Establish

goals for personal next steps at multiple levels—personal, family, school,

community

Early this

year, a Nonotuck Community

School parent and diversity committee member invited parents from my

four-year-old’s nearby childcare center to join Nonotuck parents for a

three-part racial justice workshop led by ACT for Social Justice’s Angela Berkfield and Shela

Linton. I could not have been readier.

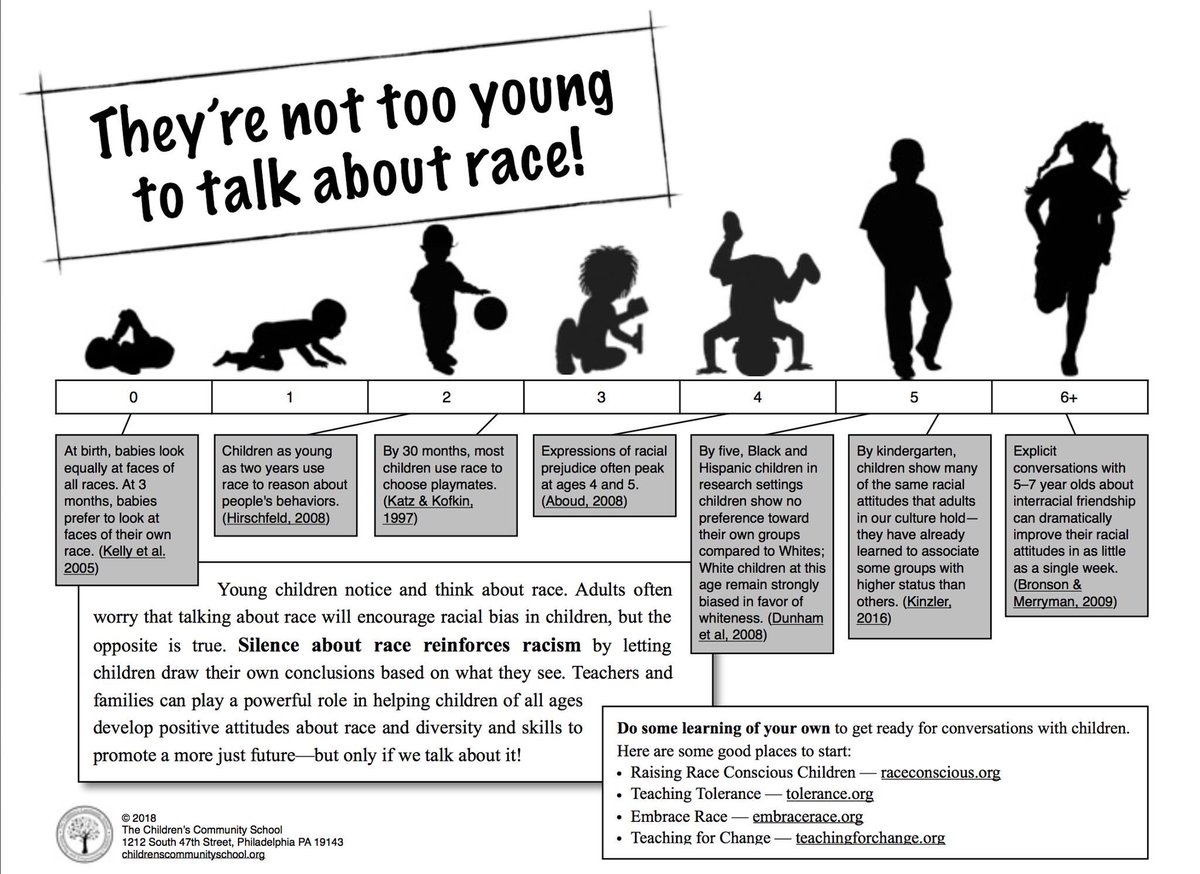

Although I haven’t to date done much of what I’d consider racial justice work, I’m an empath and avid reader/defender of social justice topics at large who feels pulled from deep down to fight oppression—and I want to raise my kid with a solid understanding of racial inequity and the need for justice. I’ve been addressing skin color and unequal treatment with my five-year-old for years, guided largely by resources I’ve found online, but I often feel like I’m muddling through, unsure my approach is as helpful as it could be.

Back in January, I was also fresh off a conversation with a white male neighbor that had included sentiments along the lines of it’s not like I’m a racist and why would I talk to my four-year-old kid about racism? It’s not his fault. The exchange had been pretty uncomfortable for me, and although I’d felt true to myself throughout, I was shaken: angry and discouraged over my neighbor’s narrow view, and second-guessing parts of my response.

In short, I was craving support—both in my parenting and as a white person who wants to deepen my understanding of white privilege and its role in my life, ultimately so that I can serve as an effective ally to people of color.

On walking into the classroom where the workshop would be taking place, I found a roomful of parents who in the coming weeks I’d get to know a bit—and learn from a lot. Chairs had been set up in a semicircle. An image of an iceberg representing two forms of white supremacy was prominently displayed—the version that is overt/widely socially unacceptable (hate crimes, swastikas, racial slurs) and the one that’s more covert/socially acceptable (hiring discrimination, mass incarceration, “colorblindness”).

Shela and Angela introduced themselves and their intent with the workshop. We talked about the iceberg metaphor, and we participants introduced ourselves, specifying racial identity, pronoun preference, and what brought us to the workshop. People, most of us identifying as white, mentioned feeling disappointed at the lack of racial justice programming at their kids’ schools, family members who make offhanded racist remarks, not knowing where to start in talking with their kids about inequity, disconnect in the value they and their partner place on having these conversations…

Although I haven’t to date done much of what I’d consider racial justice work, I’m an empath and avid reader/defender of social justice topics at large who feels pulled from deep down to fight oppression—and I want to raise my kid with a solid understanding of racial inequity and the need for justice. I’ve been addressing skin color and unequal treatment with my five-year-old for years, guided largely by resources I’ve found online, but I often feel like I’m muddling through, unsure my approach is as helpful as it could be.

Back in January, I was also fresh off a conversation with a white male neighbor that had included sentiments along the lines of it’s not like I’m a racist and why would I talk to my four-year-old kid about racism? It’s not his fault. The exchange had been pretty uncomfortable for me, and although I’d felt true to myself throughout, I was shaken: angry and discouraged over my neighbor’s narrow view, and second-guessing parts of my response.

In short, I was craving support—both in my parenting and as a white person who wants to deepen my understanding of white privilege and its role in my life, ultimately so that I can serve as an effective ally to people of color.

On walking into the classroom where the workshop would be taking place, I found a roomful of parents who in the coming weeks I’d get to know a bit—and learn from a lot. Chairs had been set up in a semicircle. An image of an iceberg representing two forms of white supremacy was prominently displayed—the version that is overt/widely socially unacceptable (hate crimes, swastikas, racial slurs) and the one that’s more covert/socially acceptable (hiring discrimination, mass incarceration, “colorblindness”).

Shela and Angela introduced themselves and their intent with the workshop. We talked about the iceberg metaphor, and we participants introduced ourselves, specifying racial identity, pronoun preference, and what brought us to the workshop. People, most of us identifying as white, mentioned feeling disappointed at the lack of racial justice programming at their kids’ schools, family members who make offhanded racist remarks, not knowing where to start in talking with their kids about inequity, disconnect in the value they and their partner place on having these conversations…

After

introductions, everyone paired up with an “accountability buddy” to identify

and discuss goals at the personal, family, school, and community levels—goals

that we committed to check in with each other on. For example, my buddy, who

identifies as white, intended to dig deeper with a relative to try to get at

where he was coming from with his racially insensitive comments, and I planned

to email the principal of a local elementary school with a reputation for its

social justice programming (“how are you doing it?”) in hopes of eventually

bringing my findings to the administration of the school my own kid would be

attending in the fall.

The rest of

the session was equally engaging: participants shared more encounters they’d

had around race and difference, as did Angela and Shela, whose deep

understanding of the complexities and reach of white supremacy was and would

continue to be a gift. Three hours in, we closed (as we would each of the three

sessions) with a reading of this bell hooks quote, which was posted on the

wall: “Beloved community is formed not by the eradication of difference but by

its affirmation, by each of us claiming the identities and cultural legacies

that shape who we are and how we live in the world… We deepen those bondings by

connecting them with an anti-racist struggle.”I left the classroom with a full brain and a full heart, and confirmation that I was most definitely in the right place at the right time. The following insight, offered by our facilitators, was already lodged, and I knew it would stay with me:

As a white ally doing racial justice work, you’re going to mess up. It’s inevitable, and it’s OK—just learn from it, adjust your approach, and keep doing the work.

Also: It helps to get comfortable with discomfort.

Workshop sessions two and three also resonated.

There was

discussion of an excerpt from Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? and a

piece, “Raising Issues of Race with Young Children,” from the anthology Rethinking Early Childhood Education. In the

latter, an educator recounts initiating an activity among first-graders that

involved acknowledging difference in skin color—an activity that one African

American girl didn’t want to take part in because she knew her darker color

would stand out.

One

workshop participant, who identifies as white, shared that, in reading, she’d

really felt for the girl—a girl who was put in a position that was clearly

uncomfortable for her. And it was the same woman who later added that she

understood that not acknowledging visible difference (read: the “colorblind”

approach adopted widely to date, including by my own well-meaning parents in

the ‘80s) had clearly not led to a comfortable existence for people of color at

large.

Referencing

the same anthology piece, I expressed some sympathy for white teachers called

on to initiate conversations about race and racism with kids, including kids of

color: “It just can’t be easy—especially for teachers who are new to this, who

just haven’t really done it before.”

We compared

notes about children’s books that reflect race and racial justice (both those

that do it well and those that fall short), and I scored a stellar rec in the

process. And for what I think was my favorite exercise of the workshop, we

split into groups to act out challenging conversations of our choosing. My

group sought to explain to a four-year-old and an eight-year-old the

significance of the Black Lives Matter sign in their front yard. Two of us were

parents and two were kids—and we “parents” definitely felt the challenge. Other

groups tackled talking to kids about a play their family had attended in which

the only person of color had played the “bad guy,” and sitting down with a

school principal to make good on the PTO’s desire to bring racial justice

programming to the curriculum—all scenarios drawn from participants’ actual experiences.

I found the

practice (and the feedback) really helpful, and I got tips from others’ role

playing too. Also, something we’d discussed before came up again: the fact that

it’s always an option to clarify or “change

course.” If we don’t manage to explain our position on something well or as

intended, or if we find our thinking changes, we can just say so. I’ve done

this with my kid and expect to do it plenty more. (“Hey remember the other day

when you asked about X—well, I’ve thought about it some more, and actually…”)

The

concluding workshop session centered on racial justice action. We brainstormed

plans at the personal, family, school, community, state, national, and global

levels, writing our ideas on large sheets of paper taped to the wall then going

around marking other actions that also resonated with us. It was awesome to see

everything that was generated in such a brief period, including:

·

Recognizing my own white privilege and continuing

to do personal work/reading/etc

·

Working to connect my passions with actions I can

take

· Connect regularly with my partner on our approach

to talking about racial justice with our kid

·

Activism/support for targeted undocumented people

·

Get involved in community organizing activities

As we gathered

for a last sit-down together, one white participant shared how sad and angry

ongoing racial injustice makes her feel, which was met with a roomful of nods

and yeses and Angela’s thanking her for inviting feelings into the room. I was struck,

too, by another person’s suggestion of opening race conversations that feel

hard with language like “this isn’t easy for me to bring up/talk about, but it

feels important and so I’m going to do my best.” I’ll be using that myself.

We talked

about our desire to welcome more people of color, both kids and staff, into the

childcare centers our kids attend and ways we can support this. Shela offered

valuable insight from the perspective of a parent of color in the Brattleboro,

VT area, sharing that in her community people of color tend to rely on

word-of-mouth when it comes to making decisions about where to send their kids.

And at the top of the list of specific considerations: would their child be in

the company of other kids of color; is the curriculum/programming strong and

does it respect and address the unique experiences of kids/families of color;

are people of color represented in staff makeup; and further down the list,

cost. (Shela shared that even when money is tight, parents of color will often

make it work if it means sending their kid to a school they feel really good

about.)

We also

talked about our professional backgrounds and how we can drive racial justice

progress through our jobs. As we’d done throughout the series, we made

connections. Knowing the workshop was about to end, we made plans to keep in

touch—and I will be following through.

Since the

conclusion of the series, I’ve thought a lot about my experience. I’ve thought about how finely

tuned and effective Angela’s and Shela’s approach as facilitators had been.

They’d created an environment that felt safe and inviting, nonjudgmental—accommodating

of everyone, no matter where we were at on our path. They’d kept us in the

racial justice space, steering us back when topics of gender got too much play.

And although warm, the two hadn’t jumped in to respond to participants’

observations with nods and other affirmative gestures intended to make a

speaker feel more comfortable in talking about difficult topics, which I’ve

realized is something I see (and do) a good deal of. Neither were they quick

to challenge directly what people shared, even when a more nuanced perspective

might aid growth. They listened—really well. That’s not to say they didn’t

contribute substantially, because they did. They just did so in a way that gave

us participants room to stretch our thinking and perhaps arrive at a different

conclusion more organically, on our own.

For

example, they emphasized throughout the workshop that no matter how challenging

and uncomfortable racial justice work may feel at times for white allies, people

of color always have it harder—and the emphasis took root. To paraphrase one

participant toward the end of the last session: I think back to my 20s, to

before I had kids. It felt like such a wide open stretch—I had more time and

space and less stress and fatigue compared to today. And now, it occurs to me

that people of color don’t generally get a stretch like that at all—they’ve had

to fight through every period of their lives.

I’ve since

thought about my comment on how race conversations likely aren’t easy for white

teachers—and I now see clearly that something far less easy is being a person

of color in a world in which white supremacy continues to reign. And while that

doesn’t mean white people’s difficulties can’t be

acknowledged, reminding myself of the relative ease that white privilege

affords is helping and will continue to help me push past anxiety brought about

by unfun exchanges like the “why should I?” one with my neighbor earlier this

year.

Speaking of

white privilege/precedence, I recently realized that, in talking about race, I

don’t yet think to share my own racial identity off the bat. For instance, the

other week I emailed an Asian American acquaintance, racial equity advocate,

and successful children’s book writer/illustrator for her insight into my

potentially representing kids of color in a story I’d written. While I’d felt

good about reaching out, it didn’t occur to me until after hitting send that

I’d failed to note (because there was a good chance she wouldn’t remember me)

that I was inquiring as a white woman. But it did occur, and I followed up.

I’ve also

kept in touch with my accountability buddy from the workshop—we became fast

friends and are working together, along with other likeminded parents, to drive

the change we want to see at our kids’ schools. And on recognizing that it’s

time, I’m deepening conversations with my kid about racial inequity, who the

other day asked about jail. I took the opportunity to introduce the concept of

mass incarceration, encouraged by a fellow workshop participant who recently

raised another “advanced” topic with her kid: the fact that police officers

often treat people of color differently, and far worse, than they do white

people.

Prompted by

the assigned reading Stages of Racial Identity Development, I’m

thinking about my place on the continuum. I want to better understand and work

through my own blocks that hinder my capacity to serve as a white ally to

people of color. I want to listen more.

And: Get comfortable with discomfort.

I’m working on it.